Artykuł partnerski

In recent decades, the whole world has been operating in an increasingly complex geopolitical environment with the global players deploying strategies in order to protect their security. Trade disruptions are increasingly likely and strategic dependencies result in economic security concerns.

In the US, calls in favor of decoupling from China have increased in recent times. The EU has sought to avoid discussion about decoupling from China, but at the same time mitigates US pressure by framing the debate around the notion of de-risking, which has become an organizing principle for the EU since it was first put forward by President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen in a speech at the World Economic Forum (WEF) annual meeting in Davos in January 2023.

According to EU officials, de-risking is motivated by a desire to reduce reliance on a single supplier or to protect against potential economic or geopolitical events. It involves diversifying supply chains, identifying alternative sources of goods and services, and implementing measures to reduce exposure to potential disruptions. Unlike decoupling, de-risking seeks to continue basic trade and investment activities—once the risks have been dealt with.

Following the emergence of the EU’s de-risking strategy in March 2023, Chinese experts and Chinese authorities expressed the view that the real purpose of the de-risking approach was “de-Chinaization,”1 as it seems the policies implemented do not aim to reduce any dependencies in any third countries but mainly focus on a single supplier, which is China. Similarly, a Chinese official has argued that the de-risking or decoupling approach to China was a way for the West to impede the regular functioning of international supply chains.

EU-China trade relations

According to Eurostat and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis, as of today the US remains the EU’s most important economic partner. Only for imports of goods does China stand out as more important for the EU in relative terms than the US. In 2023, China was the largest partner for EU imports of goods (20.5% of total extra-EU imports) and the third largest partner for EU exports of goods (8.8% of total extra-EU exports). Much of the debate on EU exposure to China focuses on imports of strategic products but many European experts and officials insist that there are other forms of exposure.

Over the past two decades EU imports from China increased almost three times faster than imports from the rest of the world. An important part of the EU’s increased exposure to China is the logical result of China’s explosive economic growth during that time. The total size of the Chinese economy (18% of global GDP) is larger than that of the EU (17%), although still behind that of the US (25%). The total value added produced by the Chinese manufacturing sector (a 31% global share) is about equal to that of the US and the EU combined. Parallel to its economic growth, China has rapidly become the leading global goods exporter (from 5% of global exports in 2000 to 18% in 2022). At the same time, the EU is still the world’s number one global exporter (as of 2022), thanks to stronger services exports. This prominent position in international trade (about equal to China, but significantly ahead of the US) continues as a strongpoint for the EU in an increasingly competitive and complex geopolitical environment. The composition of these imports changed in quantity and quality and aligned with China’s manufacture growth and upgrade. In 1995, textiles, shoes, toys, et cetera represented about 40% of EU imports from China, but today imports from China have shifted towards product groups of a more critical nature, such as electronics and pharmaceutical ingredients.

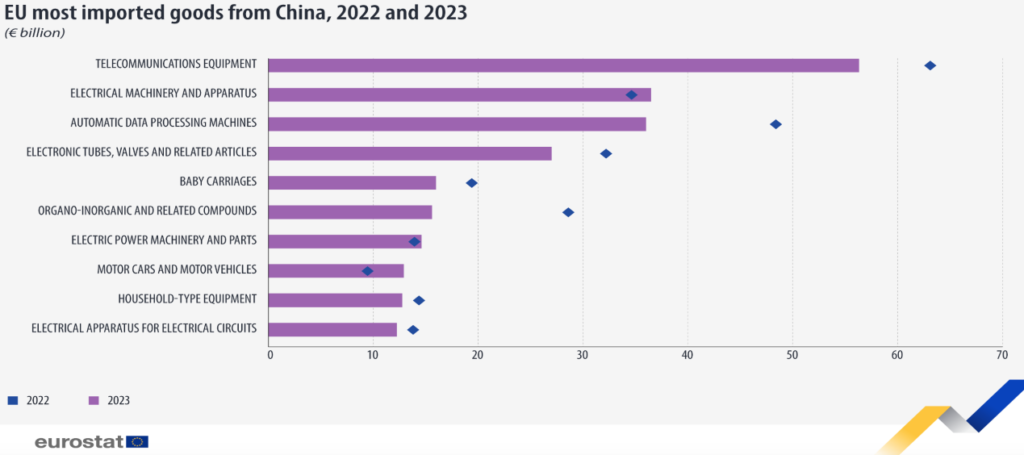

When it comes to the most imported products from China, telecommunications equipment was the first, although it went down from €63.1 billion in 2022 to €56.3 billion in 2023. Electrical machinery and apparatus (€36.5 billion) and automatic data processing machines (€36 billion) were the second and third most imported goods, respectively. Motor cars and motor vehicles registered the highest increase in imports (€3.5 billion, 36.7% more than in 2022), while organo-inorganic and related compounds recorded the largest decrease (-€13 billion; 45.4% less than in 2022).

Román Arjona, William Connell, and Cristina Herghelegiu2 developed an enhanced bottom-up and data-driven methodology to detect EU strategic dependencies using highly disaggregated product-level trade data. Their analysis identified 204 products (HS63) in sensitive industrial ecosystems where the EU experiences an important level of foreign dependencies (rare earth metals, molybdenum, borates, uranium, silicon, permanent magnets). These 204 products represent around 9.2% of the total extra-EU import value. When it comes to origins, China represents about half of this value, followed by the US and Vietnam with 9% and 7%, respectively. In the number of dependent products, China is the first source for 64 of them, followed by the US with 38 and Russia with 15. Examining the number of products rather than the value of imports is crucial since goods, despite facing low import values, may cause significant disruptions to society.

The majority of the EU’s strategic dependencies on China and the US present particularly high risks as global single points of failure (“SPOFs”). A single point of failure (SPOF) is a part of a system that, if it fails, will stop the entire system from working. SPOFs are undesirable in any system with a goal of high availability or reliability, be it a business practice, software application or other industrial system. Contrary to the EU’s dependencies on other third countries, the large majority of the EU’s dependencies are on China and the US.

EU member-states approach on the de-risking strategy

In May 2024, the European Think Tank Network on China (ETNC)–a network of experts from leading think tanks across Europe–published its annual report which examines in detail how the de-risking from China has been implemented at the national level. Among EU Member States, the Netherlands (€117 billion), Germany (€95 billion), and Italy (€48 million) were the largest importers of goods from China, with Czechia (43.7 %) having the highest share for China in its extra-EU imports. The three largest exporters to China in the EU were Germany (€97 billion), France (€25 billion), and the Netherlands (€22 billion). Germany (13.6 %) had the highest share for China in its extra-EU exports.

While de-risking narratives in the EU have thus far focused on China, they are often contextualized in broader discussions on economic security. Countries vary in their understanding and interpretation of the concept, as well as in how they distinguish it from de-coupling. The EU efforts to shift from decoupling to de-risking appears to have been embraced in many countries, at least rhetorically. One probable reason why many countries prefer de-risking over decoupling is the relative ambiguity and flexibility of the de-risking concept.

Does de-risking strategy from China serve the EU’s strategic autonomy?

Globalization is entering a new phase. Proponents of “slowbalization”4 suggest that the world is experiencing a deceleration in trade liberalization as nations pull back from endorsing open trade, a trend that may be amplified by the current de-risking narrative and could further deepen geo-economic divisions. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook, published in July 2023, forecasts a decline in trade growth. Some onlookers have raised concerns about the potential effects of de-risking on the global economy. An accelerating economic security agenda could precipitate economic fragmentation and reshape the global order.

In this context, the EU seeks strategic autonomy5, which is often confused with sovereignty, independence, unilateralism, and at times autarky. What autonomy does not necessarily entail is independence, less still unilateralism or autarky. In fact, in so far as multilateralism is a defining feature of the EU’s internal constitution and external identity, its instinct will always be to act with others. However, European strategic autonomy is contested. A first criticism6 is that the EU simply cannot become autonomous in the foreseeable future, certainly not in the critical field of defense where dependence on the US will remain a defining feature. Two less frequently articulated objections to European strategic autonomy seem more pertinent. The first is the risk that the pursuit of strategic autonomy may facilitate an undue concentration of power within the single market by individual companies or groups of member states. The second is that strategic autonomy may indirectly fuel protectionism. On inspection, both these arguments merit attention.

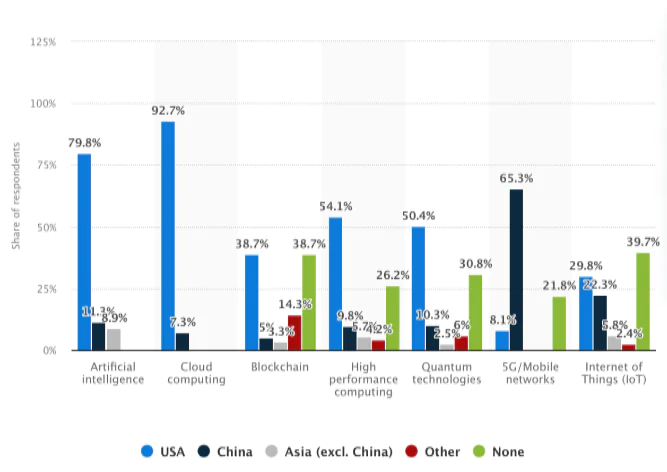

Another critical feature of European strategic autonomy is that the EU’s economy is dependent on the US, as the European Union and the United States have the largest bilateral trade and investment relationship and enjoy the most integrated economic relationship in the world. Although overtaken by China in 2020 as the largest trading partner specifically for goods, when services, technology and investment are taken into account, the US remains the EU’s largest trading partner by far. Especially in the critical and sensitive area of technology, the EU is highly dependent on the US as shown in the chart below.

Regarding the 204 identified products HS6, the US is the second source for 38, of which many are SPOFs. Moreover, total US investment in the EU is four times higher than in the Asia-Pacific region and EU foreign direct investment in the US is around 10 times the amount of EU investment in India and China together.

It is clear that the European Union and the United States, as two of the largest economies in the world, are large trading partners and their economies are increasingly intertwined and creating strong dependencies in various sectors, as described above. This close and imbalanced relationship, as it was formed after the Second World War between the US and the EU, without any doubt does not contribute to the strengthening of the EU’s strategic autonomy.7 But in its pursuit of greater strategic autonomy for Europe, by implementing its “de-risking” strategy, the EU focuses its attention on China.

From July to October 2023, the CCCEU,8 in collaboration with Roland Berger, conducted a questionnaire survey on about 180 Chinese enterprises to learn about their first-hand experience and insights from the EU market. Chinese enterprises’ overall rating for the EU business environment dipped for the fourth year but with a mitigated decline, but despite the challenges, 83% of respondent enterprises confirm that they still have faith in the EU market and will continue to expand their presence. The survey also shows that Chinese enterprises believe that the EU’s “de-risking” strategy and trade barriers will harm both China and the EU and impede global economic recovery. In the survey, 76% of respondent enterprises report that their business operations have been negatively impacted by the EU’s “de-risking” strategy.

The EU’s “de-risking” strategy is causing economies across the world to consider nearshoring supply chains. To better develop the business in the European market, enterprises will have to build a regional supply system and face higher operational cost and higher operational risk. Fragmentation of the global market will result in overcapacity in certain areas and harm the long-term prospects of industries.

While trying to lessen its dependency on China and associated vulnerabilities in a number of areas, the EU is fully aware that engaging with China is essential to combat certain global challenges, most notably climate change, but also other issues. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Europe is increasingly concentrated on greenfield investments in the mobility ecosystem. Europe is also reliant on China for solar panels, as approximately 95% of the solar panel modules installed in the EU come from China. Therefore, “de-risking” from Chinese suppliers might hamper the EU’s green energy growth.

A significant proportion of EU goods exports to China contains US inputs. As a result, the EU may be affected by tighter controls by Washington on US exports to China, as these also apply to EU companies whose exports contain “critical” US inputs. France is among those EU countries that use the highest proportion of US inputs in their exports to China. Given the high proportion of Chinese inputs in EU exports to the United States, the EU and EU companies are also at risk from tighter controls introduced by China on their exports to the United States, which mirror those implemented by the US administration. In this case as well, France is one of the EU countries with the greatest exposure.

“De-risking” from China will destabilize the EU’s own industrial chains. Recent years have witnessed many Chinese suppliers climbing up industrial chains through technological breakthroughs, capacity building, and lean operations and becoming indispensable links in global supply chains. Respondent Chinese enterprises in the CCCEU’s survey believe that forced “decoupling” and “de-risking” will erode the EU’s capability to drive economic recovery. In addition, as Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the Director-General of the World Trade Organisation, said, a decoupling between China and the EU would cause the global economy to suffer a loss in the region of trillions of dollars, or up to 2% of global GDP.

In December 2023, when Chinese President Xi Jinping met with President of the European Council Charles Michel and President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, he highlighted that China is willing to treat the EU as a key partner in economic and trade cooperation, a priority partner in scientific and technological cooperation, and a credible partner in industrial chain supply chain cooperation, in pursuit of mutual benefits and win-win results, and to realize common development.

In the same spirit, in June 2023 during a meeting with representatives of major German internationals in Berlin, Chinese Premier Li Qiang noted that “it is understandable that all parties have their own security concerns” and that “what is important is how to reasonably define and guard against risks.” He believed companies should take the leading role in risk prevetion, as “enterprises have the most direct and acute sense of risks and know how to avoid and respond to them.” He also urged continued collaboration, stating that the biggest risk is “failure to cooperate.”

With both the Chinese and EU sides acknowledging the need to maintain collaboration and hedge against risks, the outcome of the EU’s new position will ultimately depend on how far the EU will push the concept and how the strategy will be implemented. The question of several Member States, governments, and experts is how exactly the EU could implement a “de-risking” strategy with China without foregoing the benefits of trade. The standard answer is that the EU should identify product-level trade dependencies, mainly on the import side, and reduce them, mainly through diversification of suppliers, while otherwise maintaining maximum trade integration.

Footnotes

- CCCEU report on the Development of Chinese Enterprises in the EU 2023/2024 “Building Trust, Boosting Prosperity”

- “An enhanced methodology to monitor the EU’s strategic dependencies and vulnerabilities”, Single Market Economics Papers, Working Paper 14, European Commission

- The World Customs Organization’s Harmonized System (HS) uses code numbers to define products. Six-digit codes are the most detailed definitions that are used as standard.

- CSIS: “A closer Look at De-risking”, by Emily Benson and Gloria Sicilia, 2023

- Instituto Affari Internazionali: “European Strategic Autonomy: What It Is, Why We Need It, How to Achieve It”, by Nathalie Tocci, 2021

- Instituto Affari Internazionali: “European Strategic Autonomy: What It Is, Why We Need It, How to Achieve It”, by Nathalie Tocci, 2021

- Clingendael Report: “European strategic autonomy in security and defence”, by Dick Zandee, Bob Deen, Kimberley Kruijver and Adája Stoetman, December 2020, pp. 45-46

- China Chamber of Commerce to the EU

Dr. Pelagia Karpathiotaki is post-doctoral researcher at the University of Piraeus (Greece), senior researcher at the Academy of China Open Economy Studies (ACOES) – University of International Business and Economics (UIBE). She also teaches Phd and Master Degree students at UIBE University and Shangdong University of Technology.